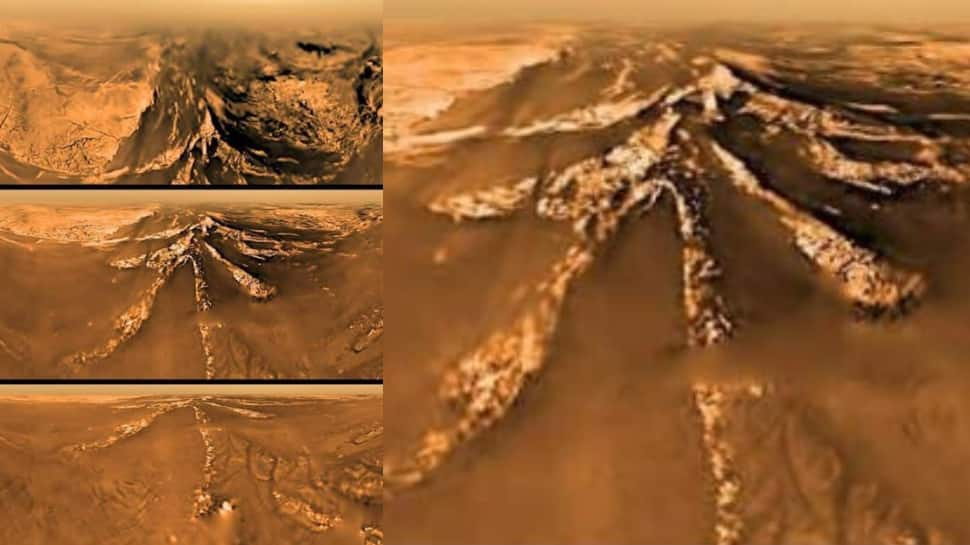

In January 2005, the Huygens probe, part of NASA's Cassini mission, made history by landing on Titan, Saturn's largest moon. This marked a significant achievement as it became the first and only probe to touch down on a celestial body so distant from the Sun. One of the most captivating aspects of this mission was the image captured at just 8 km above Titan's surface, revealing peculiar branching channels that have puzzled scientists for two decades.

These channels, resembling river systems observed on Earth, emerge from the frigid environment of Titan, where temperatures drop to an inhospitable -179°C. Despite their appearance, researchers have had to rethink the concept of fluid flow, as liquid water cannot exist under such conditions. Instead, methane takes the role of a fluid on Titan, mirroring water's behavior on Earth in its processes of evaporation, cloud formation, and precipitation.

Upon landing in the Adiri region, which looks like a desiccated delta, the Huygens probe collected data through its Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR). The imagery suggested that these channels could be remnants of ancient methane floods, sculpted by seasonal methane rains, or possibly the result of cryovolcanic activity that forces icy slurries to the surface. While laboratory studies support these theories, they also leave many unanswered questions regarding the timeline and nature of these formations.

Beyond the mystery of the channels, Titan's composition and atmospheric conditions continue to intrigue scientists. The analysis revealed an atmosphere composed of 98.4% nitrogen and 1.4% methane, which is reminiscent of Earth's primordial atmosphere. Additionally, complex organic molecules known as tholins, formed from methane exposure to sunlight, could provide insights into prebiotic chemistry.

Huygens operated for merely 72 minutes after landing but delivered invaluable data that reshaped our understanding of Titan. This short timeframe limited observations of the landscape, leaving many elements of Titan's surface, including the aforementioned channels, shrouded in uncertainty. Future missions are now set to explore these enigmas further.

The upcoming Dragonfly mission, scheduled for launch in 2028, aims to delve deeper into the mysteries of Titan. Unlike Huygens, Dragonfly will be a rotorcraft capable of flying to various locations across Titan's expansive sandy terrains. Its objectives include a comprehensive study of the moon's organic chemistry, an investigation into potential life-sustaining processes, and a detailed analysis of ancient, untouched terrains spanning millions of years. With its advanced capabilities, Dragonfly is expected to transform our understanding of Titan, turning a single enigmatic photograph into a prolonged and fruitful planetary exploration.

In conclusion, the questions surrounding Titan's branching channels remain tantalizing puzzles for scientists two decades after Huygens' successful landing. As we prepare for the Dragonfly mission, it is clear that the secrets of Titan will continue to unfold, potentially revealing crucial insights about both the moon itself and the broader context of planetary evolution.